The following is an article originally posted on Medium that we thought was an interesting real world case of crypto being used widely in a specific geographic location, in this case Portsmouth, NH. This shows the real possibility of using crypto in Black communities all over the world to begin to take back control of our economies.

by Drew Millard

A tour of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where cryptocurrency diehards are leaving the U.S. dollar behind

The people of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, have always hated rules. A shipping town first settled in the 17th century, Portsmouth was by 1864 home to 120 bars, 30 brothels, and three police officers. It’s a place where a young exhibition shooter named Annie Oakley spent her summers giving free shooting lessons to women, and it’s a place where Blackbeard, among other pirates and privateers, allegedly left buried treasure.

Today, it’s a place where a Tesla Model X SUV bearing the state’s “Live Free or Die” plates zooms by as I walk to the Seacoast Repertory Theater, the lobby of which houses a Bitcoin ATM.

When I arrive, I quickly discover that the term “Bitcoin ATM” doesn’t mean it’s a thing you stick a debit card into exchange for Bitcoin. Instead, it’s a cube that eats your cash and spits Bitcoin into a cryptocurrency wallet app on your phone. Which means that to buy cryptocurrency at this Bitcoin ATM, I have to find an actual ATM, withdraw cash, then return to the Bitcoin ATM and give it my money.

“It only takes hundreds,” says a guy in the lobby who has borne witness to my struggle. He’s a local who spends a good chunk of time at the theater and says my predicament isn’t uncommon. People come from miles away to use the thing, he adds. “Then they only have twenties… then they have to go find hundreds somewhere.”

Portsmouth is a strong contender for the most cryptocurrency-friendly city in the world.

When the machine was first installed, in December 2016, he says, “it was getting so much foot traffic.” That was around when Bitcoin began looking less like something nerdy anarchists traded for drugs and more like a sound place to park your money. In 2017, its price rose from about $900 per coin to $20,000, and with those monstrous gains came a class of investors, speculators, and entrepreneurs buying in, hoping to ride the cryptocurrency rocket to the moon.

As those interested in emerging technologies (or schadenfreude) are well aware, the bubble did indeed burst — with a resounding pop. After a dramatic early 2018 drop, Bitcoin’s price has spent the past few months hovering between $6,000 and $7,000 per, occasionally swinging up but never coming anywhere close to its previous highs.

That drop-off hasn’t stopped Portsmouth, with a population of just 21,000 people, from becoming an unlikely haven for crypto. According to CoinMap.org, the Portsmouth area is home to 24 businesses that accept cryptocurrency, including restaurants, clothing stores, juice bars, regular bars, restaurants, a yoga studio, a dance studio, a hair salon, a vape shop, and a law office. If a grocery store started accepting cryptocurrency, one resident told me, it would be possible for a person to leave the U.S. dollar behind and exclusively pay for things with a jumble of Bitcoin, Dash, Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Monero, and Zcash. While places like New York City, Amsterdam, and the Bay Area have more businesses that accept cryptocurrency on the whole, Portsmouth is a strong contender for the most cryptocurrency-friendly city in the world on a per capita basis.

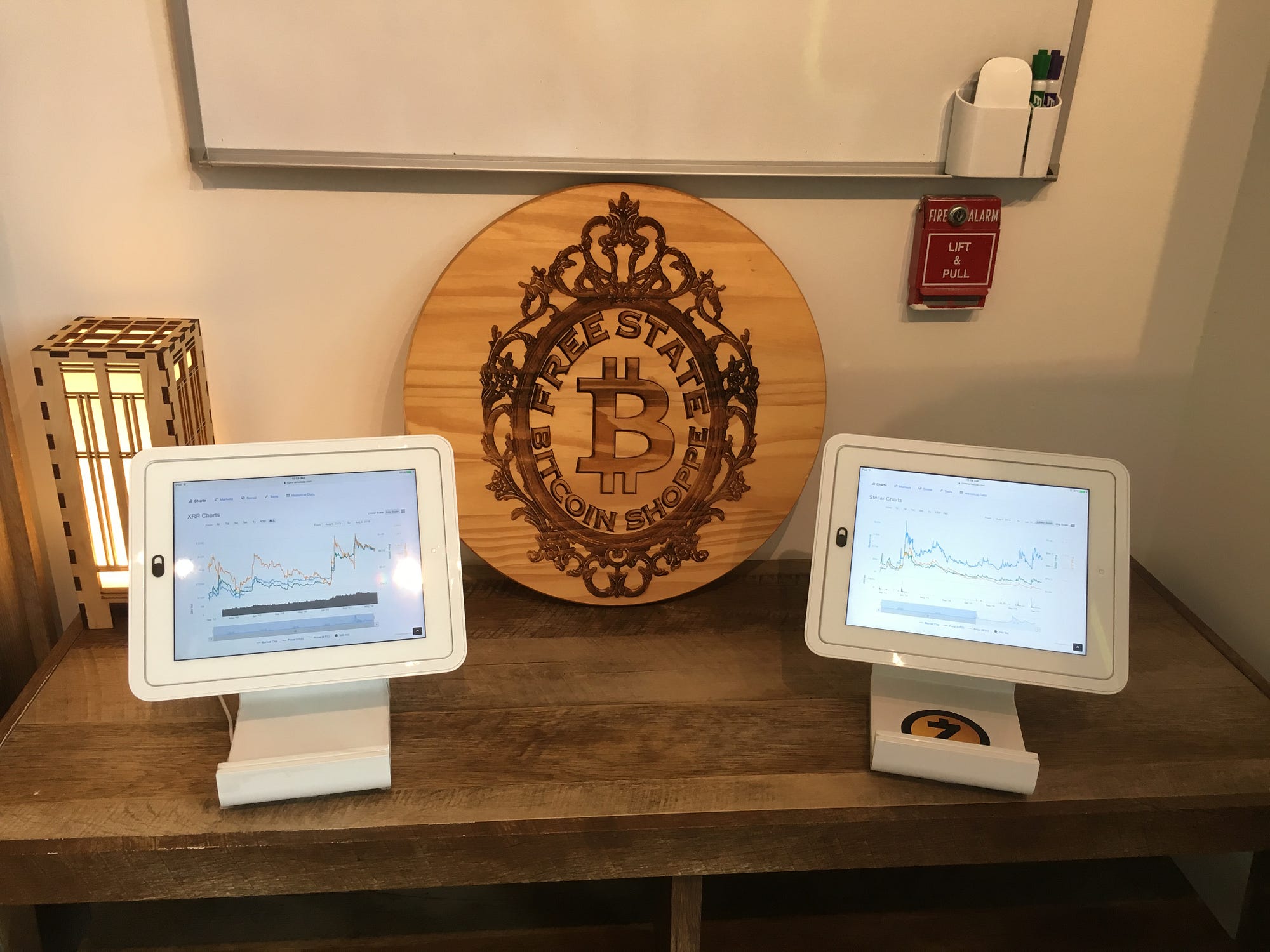

Many of Portsmouth’s cryptocurrency-friendly businesses are concentrated in a small radius near downtown, centered around the Free State Bitcoin Shoppe, an anarcho-libertarian gift store that accepts only cryptocurrency. The store is owned by Derrick J. Freeman and Steven Zeiler, a pair of cryptocurrency enthusiasts and developers who have led the charge in encouraging Portsmouth’s small businesses to jump on the bandwagon. In part, this is because they’re co-founders of AnyPay, a Square-like app that allows merchants to accept cryptocurrencies. But I don’t get the sense that they’re in cryptocurrency simply to make a quick buck.

Zeiler, according to his LinkedIn profile, spent two years as a developer at the cryptocurrency company Ripple and lists himself as having attended the Austrian School of Economics, which despite what the name implies, is not an actual educational institution, but rather a school of economic thought whose anti-government, pro-free-market slant aligns heavily with Bitcoin’s.

Freeman, meanwhile, is something of an anti-government crusader. The “about” section of his website includes an “activism curriculum vitae” that lists his work as a protester, blogger, and podcaster, as well as his multiple arrests for civil disobedience. Freeman has also uploaded dozens of filings related to his court cases and made a film about his exploits called Derrick J’s Victimless Crime Spree. He’s a member of a libertarian blogging collective called Free Keene, where he has documented his efforts to encourage kids to drop out of school, his involvement with the New Hampshire secessionist movement, and his failure to obtain a concealed carry permit from the state (in part due to his multiple arrests). For his efforts, Freeman has had at least one libertarian ska-punk song written about him.

While planning my trip to Portsmouth, I contacted Freeman and Zeiler to make sure their store would be open and to line up interviews. Only Freeman got back to me, telling me, “Our doors are open to all every day from 12 to 8,” but that he’d “have to pass” on an interview.

“If I have two minutes with somebody, they’re walking out with a Bitcoin wallet.”

When I arrive at Free State Bitcoin Shoppe, I’m greeted with a sign on the door that reads, “Open by appointment,” along with a phone number. I can’t see anyone through the window, but I try the door just in case. It’s locked. Through the window, I see that the walls are lined with framed photos of Ayn Rand, Andrew Jackson, Edward Snowden, Friedrich Hayek, and Ross Ulbricht.

Never in my life have I wanted so badly to jump through a glass door like I’m Bruce Willis in a Bruce Willis movie and ask whoever’s on the other side what their deal is, and also if their Bitcoin ATM will take my debit card. Instead, I call the number on the door. A robotic voice tells me the current price of Bitcoin and instructs me to leave a message. I comply with the robot’s orders and pray to Blockchain Jesus that someone gets back to me.

Economists generally agree that money is defined by three features: It’s a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. If I give my friend a T-shirt in return for a thing, and that thing is quantifiable and can be used to purchase a six-pack from a nearby bodega, and the bodega guy is confident that, in one month’s time, he will be able to transfer the thing I’ve given him to someone else in exchange for as much cat food for his bodega cat that he would be able to buy today, then the thing is money.

Cryptocurrencies don’t necessarily pass the money test today, at least for society on the whole, though they have the potential to be defined as money — and indeed are designed to be used as such. You could say that cryptocurrencies have become victims of Bitcoin’s success. The currency’s history of roller-coaster prices has created the precedent for Bitcoin to spike again, and even higher next time. Nobody wants to spend their Bitcoin on a can of cat food today when that same amount of Bitcoin might be able to buy a whole litter of Russian Blues tomorrow.

“The overwhelming majority of people aren’t looking to sacrifice brand loyalty for utopian ideals,” an entrepreneur friend told me recently. In this case, the brand we’re all loyal to is the U.S. dollar. But if the dollar were to experience a rush of instability, Bitcoin, many of its cheerleaders hope, would be ready to step in and take its place.

“If people like a more peaceful, voluntary world, I think they should use a currency that represents their values.”

This isn’t outside the realm of possibility. The stock market is on a bull run that hasn’t let up for nearly a decade, but it has to stop at some point. Between technical indicators of a looming bear market, a potential subprime auto-loan crisis, and the ongoing likelihood that Donald Trump will destabilize the market through his rash actions, there are plenty of reasons to believe that our economy might go into a tailspin.

Were such a scenario to occur, Bitcoin — a peer-to-peer currency, forged in the wake of the previous decade’s financial crisis, whose value isn’t contingent upon debt, corporations, or the actions of a single government — might suddenly seem like a very attractive form of money. While it’s estimated that there are 3 million to 6 million active Bitcoin users throughout the world, it’s hard to tell whether they’re actually spending the stuff IRL or if they’re simply holding onto it, hoping its value in dollars will rise. But if we were all to suddenly use Bitcoin every day, that metric wouldn’t necessarily matter — rather than viewing Bitcoin’s price in relation to the dollar, we’d instead view Bitcoin’s price in relation to things we used to buy with dollars.

My visit to Portsmouth was, in a sense, an attempt to glimpse into this one possible future.

For all the potential that cryptocurrencies hold for tomorrow, they’re a royal pain in the ass to use today. I had about $55 in Bitcoin and $20 of its cheaper, faster offspring Litecoin ready for my Portsmouth adventure, but due to the Bitcoin network’s slow rate of transactions — payments can take up to 10 minutes to go through — I decide to change my Bitcoin into Dash, another Bitcoinish cryptocurrency that prioritizes speed and privacy. To do this, I need to transfer my Bitcoin from Abra, the app where I bought it, to Coinomi, an app that has a built-in conversion feature.

But Bitcoin’s inherent sluggishness means that the process of porting and converting causes my Dash to be stalled in the digital ether at the exact moment I try to pay for my bacon-and-egg croissant at Fezziwig’s, a café located a couple blocks away from the Free State Bitcoin Shoppe.

Fezziwig’s interior, with its mirrored walls and delicate pastries, evokes 1930s France. The barista is dressed in period-era clothing, which accentuates the environs, and wears an earpiece while standing behind an iPad, which does not. Since my Dash is tied up in the cloud, I opt to pay with my Litecoin and begin the process of opening up my wallet app and scanning the QR code shown to me on the iPad, which triggers an automatic transfer out of my Litecoin wallet and into that of Fezziwig’s.

This ends up being a genuinely thrilling experience. With one last tap of the screen to confirm my purchase, I would step out of the world of banks and government-backed fiat currencies and into another, where no person or institution could stand in the way of me and my financial agency.

But there is something else keeping me from stepping into this brave new world, and that something is the fact that I don’t have any reception on my phone and therefore can’t make the Litecoin in my phone become Litecoin in Fezziwig’s iPad. I whip out my credit card and pay with the dreaded fiat instead.

“I love using things of real value with people who are giving me real value.”

As the barista, who identifies herself as Brontë, is joined by a woman who calls herself Zinnia, I strike up a conversation with them about the world of crypto commerce. “We have a pretty solid pool of regulars who know we take [cryptocurrency] and come here many times a week because we take it,” says Brontë, adding that a few of the regulars have her wallet address saved on their phones and tip her in cryptocurrency. She occasionally spends her cryptocurrency while she’s in the neighborhood. “But mostly, I’m mainly hoarding it,” she says.

Fezziwig’s cryptocurrency commerce is aided, Brontë tells me, by the fact that it’s located next to the Blockchain Institute of Technology, a center that offers crypto certification classes online. Zinnia tells me it’s run by Freeman and Zeiler, of the Free State Bitcoin Shoppe. She refers to them as the “Bitcoin Boys.” “We’re their favorite restaurant,” Brontë says.

I head next to the Blockchain Institute of Technology in the hopes that Freeman and Zeiler will be there to let me into their Bitcoin store. On the door of the Institute, a sign reads:

Students and Faculty Only

Questions?

Answers found at the Bitcoin Shoppe

(1 block from here, toward the river)

Hoping this might mean that the Bitcoin Boys are back at the Bitcoin Shoppe, I return to the store to find it empty. There are a few boxes of literature attached to the shop’s door. One contains brochures listing the businesses in Portsmouth that accept cryptocurrency; the other holds a short children’s comic book about space pirates who don’t trust the Federal Reserve. (The back cover reads, “We’re Going to Space and Government is NOT invited!”) I help myself to copies of both.

Of all the stores listed on the brochure, one called Deadwick’s, described as a “Victorian psychic parlor,” piques my interest. When I arrive, the shop’s stereo is playing the score from The Nightmare Before Christmas. It sells wands, vintage doll parts, assorted bones, potions and oils and herbs, occult books, statuettes of the Knights Templar deity Baphomet, magical soaps, tarot cards, handmade poison spoons, crystals, intricate-looking brooms, incense, and T-shirts bearing the astrological charts of the serial killers John Wayne Gacy and Ted Bundy.

I still haven’t successfully bought anything using cryptocurrency, so when I find a small silver coin with a pentagram on it, it feels like an apt purchase. This time, the phone-to-iPad process works perfectly, and in no time, I’ve exchanged about .031 Dash — approximately $5 — for my witchy token.

“To my knowledge, we’re the only witchcraft shop in the world that accepts cryptocurrency,” the clerk tells me. When I ask his name, he tells me to call him Mr. Deadwick and says that he manages the place. We begin to chat about my coin; it turns out that it’s actually called an “altar tile.” The pentagram — or pentacle, as he calls it — is “representational of earth, air, water, fire, and spirit.”

Mr. Deadwick tells me he is a certified herbalist, as well as a practitioner of chaos magic, which involves the creation of sigils: symbol that one imbues with their will to accomplish what they desire. “A sigil is personally yours,” he tells me. “It comes from your own creative mind. Therefore, creation is magic.”

Under that line of thinking, I tell him, cryptocurrency networks — intricate jumbles of code whose contents store value because of belief and will — seem a lot like sigils themselves. “Exactly,” he says. “It’s hidden. It’s secret.”

By the end of the day, I’ve toured the town, popping into crypto-friendly shops and restaurants and conducting interviews. But I still have no idea how to get in touch with the Bitcoin Boys. The closest I get to a lead is when the manager of a crypto-friendly sunglasses store tells me that if they’re not at the store, they’re probably at the Blockchain Institute of Technology. When I ask if I should knock on the institute’s door, she shrugs. “I mean, it’s a free country,” she says.

Before leaving downtown, I go ahead and knock. No one answers.

The next day, I return to downtown Portsmouth in hopes that the Free State Bitcoin Shoppe will actually be open this time. It isn’t.

As I’m getting out my phone to call the number on the door and try yet again to make an appointment, a young man wearing pressed khakis and a short-sleeve button-up shirt walks past me. He has cropped hair, a far-off look in his eyes, and a face that I recognize from spending so much time Googling the name “Derrick J. Freeman.”

“Derrick?” I say. He nods.

I tell him I’m the reporter who contacted him a while back about seeing his store and maybe doing an interview. He tells me I need an appointment to see the store. I tell him I tried to make an appointment but didn’t hear back from anyone.

He relents, unlocking the door to the shop. And despite his previous refusal to talk to me on the record, he even tells me I can turn my recorder on.

Inside, I purchase a T-shirt with the Bitcoin logo on it, a book that Freeman recommends — Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar’s Cryptoassets: The Innovative Investor’s Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond (I don’t have the heart to tell Freeman that I’ll sell my remaining crypto holdings before my article runs just in case it somehow ends up affecting the market) — and, also upon his recommendation, a pair of $20 billion bills from Zimbabwe dating from the nation’s hyperinflation crisis of the late 2000s.

“They tell a very sad story,” Freeman says, “of the folly of a money supply that’s inflationary ad infinitum. Just adding zeros to a piece of paper doesn’t make you wealthier — it doesn’t mean any new value was created in the economy.”

“With cryptocurrency, we’re not only using a different type of money, we’re using a new way of paying and doing a really different style of action.”

“I love using [things of] real value with people who are giving me real value,” Freeman says. “I liked to trade in silver before Bitcoin was around. I’d offer pieces of silver to the pizza shop down the street.” Freeman says that these days, he lives exclusively off cryptocurrency, sticking to local businesses that accept it and making arrangements to get around those that don’t. For example, since there isn’t a local grocery store that takes cryptocurrency, he employs a personal chef and pays him in Bitcoin. (The store also sells gift cards to a local grocery store for those who can’t afford such a lavish end-around.)

As we talk, passersby drop in, some greeting Freeman, others simply trying to wrap their heads around what a Bitcoin is. Though Freeman says the shop is a great way to help people understand the mechanisms that power cryptocurrency — “If I have two minutes with somebody, they’re walking out with a [Bitcoin] wallet,” he tells me — he hasn’t been as successful as he’d like.

For the past few months, Freeman has been leaving tips at restaurants in the form of slips of paper containing QR codes, which, if scanned, give what he calls a “generous” tip in cryptocurrency. However, he says, it’s rare that people actually claim the money he’s left for them.

One of the reasons it can be tough to convince people to buy into cryptocurrency, Freeman says, is that, “All the motions of a payment are ingrained in us already. But with cryptocurrency, we’re not only using a different type of money, we’re using a new way of paying and doing a really different style of action.” Besides, he says, “The way the Bitcoin price fluctuates is kind of nuts right now. When people get excited that I paid them some Bitcoin and go, ‘It went up a dollar!’ I’m like, ‘Yes. It will go down, too.’”

For most of us, putting our money into something like Bitcoin is still a leap of faith. But as someone who feels that the dollar is “an IOU essentially covered in blood,” it’s a leap Freeman is willing to take. “The value of your savings is being diminished right out from under your nose to finance war,” he says, “And that is theft.” Bitcoin, he says, “can’t be inflated to pay for bombs and tanks. If people like a more peaceful, voluntary world, I think they should use a currency that represents their values.”

That evening, I return to Deadwick’s for its Spirit of the Past Ghost Tour, a trolley ride featuring stories of the many eerie murders that have occurred in Portsmouth over the years. Seats are $32 apiece, and as I reach for my phone to pay with Dash, I realize I’ve only got about $22 in crypto left.

And so, here at Deadwick’s, I encounter yet another foible of using cryptocurrency: If you don’t plan ahead, you’re hosed. Such logistical concerns — to say nothing of the fact that exclusively using your cellphone to pay for stuff makes you complicit in a whole different set of ethical issues — create such a barrier that only a diehard would abandon the solid ground of the dollar for the choppy waters sailed by the H.M.S. Bitcoin.

As the trolley passes a graveyard haunted by the ghost of a woman who once turned into a cat, I think about how Portsmouth is a place where anything can be real if you want it to be. The money we use today is useful because we think it is. Our guide shines her flashlight out the window onto one of the headstones. Though we remain stationary, the shadow begins to creep to the left, and I begin to convince myself that it’s not a shadow at all. Who am I to say either way?